By Evelyn Lam

Staff Writer

Roads stretch like veins across a page of predominantly pale yellow grids, each strip representing family bloodlines and strings of community history. In zoning maps, yellow indicates areas reserved for single family residences. For some people, these zoning codes are a reminder of inaccessibility and exclusion.

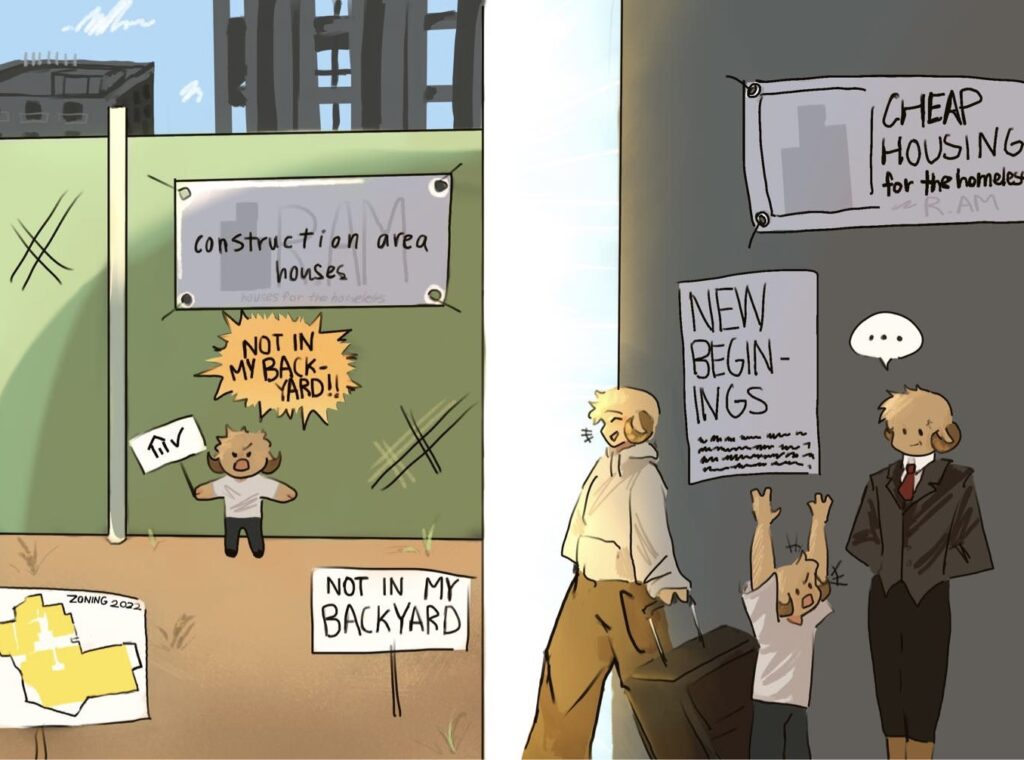

NIMBYism, short for Not In My Backyard, refers to resident opposition to construction projects in their neighborhood. These opponents, called NIMBYs, advocate against multi-family units like apartments or assisted housing projects.

In our very city, residents opposed a plan to create affordable housing for veterans and formerly unhoused individuals back in 2017. The nonprofit Mercy Housing would have converted the Golden Motel to 169 supportive housing units. Residents were afraid the project would bring in dangerous occupants and decrease property values.

However, most of these concerns are unsupported. A 10-year study published in the Journal of Housing Economics found that newly built low-income housing had no effect on property values. Instead, racist and classist biases rather than factual evidence influence these fears. While many opponents see unhoused people as unstable, most assisted housing residents are actually families, seniors, individuals with special needs and veterans with PTSD. Ignorance and dehumanization fuels the backlash against them. It’s critical to recognize the underlying prejudices of NIMBYism.

Exclusionary housing is a product of a long racist history of redlining against Black Americans. In 1917 when race-based zoning was struck down by the Supreme Court, lawmakers set minimum lot sizes and banned apartments. For Black Americans with less access to financial opportunity and generational wealth, economic segregation was practically racial exclusion.

NIMBYism doesn’t always come in the form of outright, raging bigotry. Oftentimes, it’s systemic and discreet. Our city’s zoning code includes language about regulating “the height [and] number of stories of buildings” to “limit the density of population.” These codes restrict a lot that could comfortably fit four condominiums to just one large, single-family home.

Partly because of these regulations, the median home price in Temple City has reached $1.32 million or 150% of the national average, according to the Council for Community and Economic Research. With home ownership becoming increasingly unattainable, I worry that my own financial future will look very different than my parents’. If you’ve ever thought of buying your own home or raising a family here or anywhere, costs can be a major source of anxiety.

Many of our parents made sacrifices and moved to a city like ours to break harmful cycles. Today, many others are seeking the same opportunity to escape generational poverty. It’s crucial to combat NIMBYism by expanding diversity and education.

American individualism can offer a narrow perspective and lifestyle. My parents from Hong Kong grew up in highly-dense, upzoned communities. There are drawbacks, but whenever I visit, I notice the collectivism. Everyone is a knock away from their neighbor and shares a connection with each resident. The skyscrapers we fear are the pride and beauty of their city.

When we choose diversity, our communities become significantly richer. We’re already making progress. Last year, we saw the opening of Begonia Place, a mixed-use residential project, and the city continues to provide rental assistance. We can build on these new beginnings to achieve much more.

Developments are more exciting when everyone can rejoice in them, and maps are more vivid when they’re multi-colored. The heartbeat of our neighborhood pulses stronger when we open our gates to new possibilities.